March marks the beginning of spring, a season of renewal and growth, as nature awakens with blooming flowers and longer, sunnier days. It’s also Women’s History Month, which is a time to celebrate the achievements, resilience and contributions of women throughout history.

Although it goes without saying, women have come a long way—breaking barriers and making strides in education, politics, science, technology, the arts and beyond. Their ongoing fight for equality continues to shape a more just and inclusive society, inspiring future generations to keep pushing forward.

Today we take a journey back to the 1800s, where women’s idealized role was that of a housewife, as they were expected to marry, manage household chores and raise children.

Although there were jobs available to women, most occupations were based upon social class and marital status, lest we forget that women were not conferred professional degrees or titles at that time, let alone be financially autonomous. For example, unmarried women could work as teachers, women from poor families could work as servants or in factories, women in farming communities worked outside of the home on the family farm and women from prominent wealthy families often did not work.

In the nineteenth century, most women also lacked formal education; marriage was an economic necessity as they relied on their husbands for their status and place in society. Even women that came from wealthy families were barred from higher education, as most institutions did not confer degrees to women. In fact, the first degrees awarded to women at Moravian College didn’t occur until 1915 and the first degrees awarded to women at Lehigh University occurred several years later in 1921.

Finally, the last half of the nineteenth century saw advances in women’s property rights, extending and solidifying the legal status and rights of married women.

However, in the United States, women didn’t gain the legal right to open bank accounts in their own names until the 1960s and were barred from obtaining credit cards on their own until the passage of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act in 1974, which banned discrimination based on sex or marital status.

Prior to then, banks could legally discriminate against women, requiring them to have a male co-signer to open a bank account, obtain a line of credit or take out a loan, which unmarried women were often refused. The ECOA made it illegal for financial institutions to discriminate against applicants based on gender, religion, race or national origin. With that being said, it’s important to note that the road to economic freedom was marred with much more significant barriers for Black women.

The half-century spanning from 1870-1920 also saw a shift in women’s careers as well, largely due to changing attitudes about women and a rapid increase in the number of middle-class women working outside the home. This expansion saw a rise in numerous occupations such as typists/stenographers, secretarial/office workers, telephone operators, librarians, nurses and artists. According to the 1880 and 1890 censuses, women engaged in gainful occupations rose in all occupations. For example, female artists and teachers rose from 2,061 workers to 10,810, female authors rose from 320 to 2,725, female musicians and teachers of music rose from 13,182 to 34,519, female teachers (already a female-dominated occupation) rose from 154,375 to 245,230, female nurses and midwives rose from 14,422 to 51,402, women in sales rose from 7,744 to 58,449, female bookkeepers and accountants rose from 2,365 to 27,772, female clerks and copyists rose from 1,647 to 64,048 and female stenographers and typewriters jumped to an astonishing 21,185 (although the 1880 census does not include statistics from this occupation).

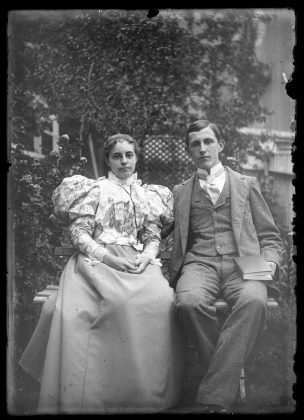

Carving out her place in history, Norma McFall Collmar was a trailblazer with many talents, who left a lasting legacy on Easton. Born Norma McFall on July 23, 1863 in Martins Creek, Pennsylvania, she soon moved with her parents, Isaac and Louisa Young McFall, to Saint Joseph’s Street in South Easton when she was a toddler.

A bright and ambitious student, Norma graduated from South Easton High School in 1881 at just 16 years old. She went on to teach in South Easton schools for six years before continuing her education. Determined to pursue her passion for music, she graduated from the Boston Conservatory of Music around 1888, where she majored in organ, piano and the directing of public school music.

Upon her return to Easton, Norma became the first supervisor of music for Easton Public Schools, bringing the joy of music to local students.

For eight years, she also served as the organist and choir director at Trinity Episcopal Church on Spring Garden Street, filling the sanctuary with beautiful melodies. Passionate about fostering community, she founded the New Century Club of Easton and led it as president and was also an active member of the George Taylor Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution, preserving and celebrating local history.

In 1894, Norma married physician Charles Collmar, who became the first surgeon on the staff of Easton Hospital. Together, they had one daughter named Rida.

It was through Norma’s passion for photography that her creative spirit truly shone through.

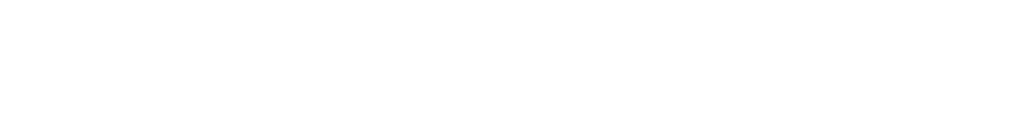

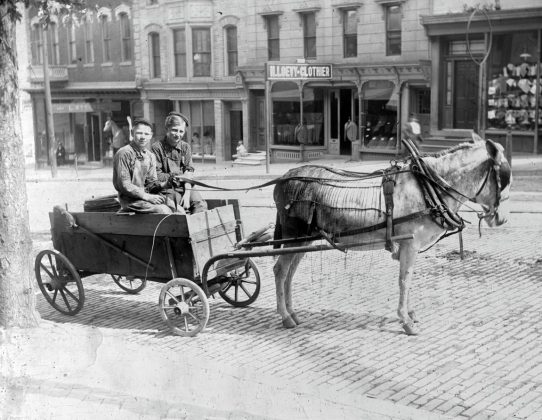

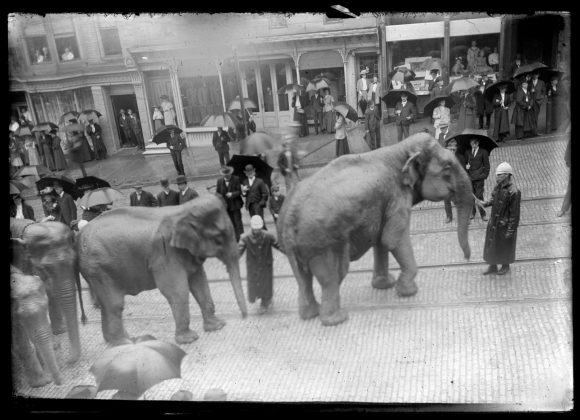

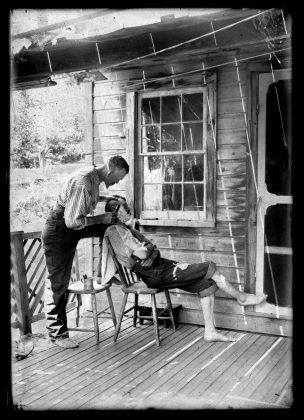

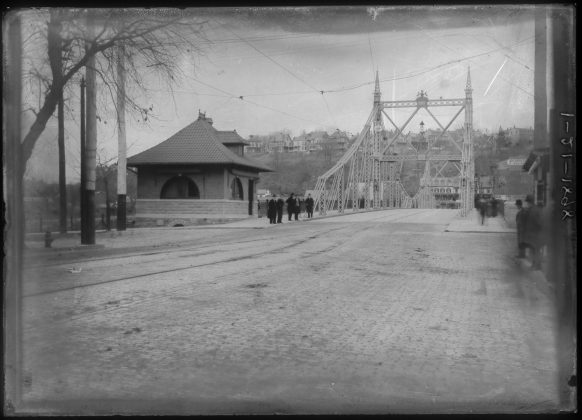

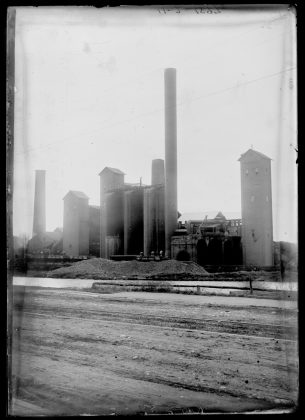

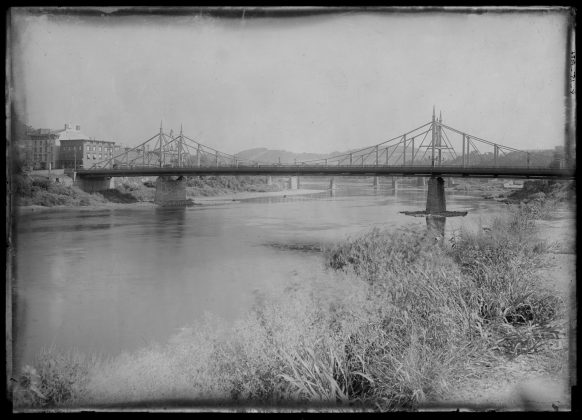

From 1887 to 1907, she roamed the Easton and Phillipsburg countryside with her 50-pound camera, a heavy case of glass negatives, a walking cane, and—ever prepared—a six-shooter pistol to scare off snakes and mischievous boys.

Her striking images captured life in the region with remarkable detail, while simultaneously making art more accessible to Northampton County.

As an amateur photographer and instructor, Norma took many pictures of Easton and vicinity in the 1890s and 1900s, documenting the world around her with an assortment of subjects. For many years, she also provided a photography magazine with its cover.

After her death on Feb. 17, 1925, all the negatives of her photographs, which were in the form of large 5×7 inch glass plates, were donated to the Northampton County Historical and Genealogical Society by her daughter. Many prints have been made from these glass plates.

Thanks to a donation of more than 50 glass plate negatives from Norma’s daughter, Rida Collmar Seastrom (1903-2000), her glass plate negative collection offers a unique glimpse into the past and can be viewed in the Decorative Arts Gallery at the Sigal Museum in Historic Downtown Easton. Additionally, a selection of Norma’s glass plate negatives can be found on the sigalmuseum.org website under online collections, thus ensuring that Norma’s artistic vision continues to fascinate, inspire and connect future generations with Easton’s rich history.

Fortunately, Norma’s life was filled with many opportunities due to her wealth, status and education. These opportunities are what enabled her to become such an avid photographer, and without which we may not have such a rare, intimate and vivid glimpse into what life was like in Northampton County the late 1800s and early nineteenth century.

The donation of Norma’s glass plate negative collection serves as a bookmark in history. Hopefully, Norma’s collection will inspire more women to be bold, be brave, be true to themselves and to not be afraid to try new things, as they, too, bookmark their place in history.